Discussions about inflation often get muddled by commentators who might look at one measure of inflation and say there is no inflation and other commentators that will focus on another and say we’re in the middle or on the cusp of hyperinflation. The truth is often balanced between the extremes. Most countries’ economies have a mix of inflationary and deflationary forces that counteract one another, with some extreme exceptions.

We can bracket inflation into three different categories: monetary inflation, asset inflation, and consumer inflation. In and of themselves these three types of inflation aren’t bad as long as there are counteracting forces that maintain or improve standards of living. However, more often than not this is not the case, and these inflations lead to stagnating and even lower standards of living for people who don’t hold assets and rely on wages denominated in government currencies for their wealth.

Monetary Inflation

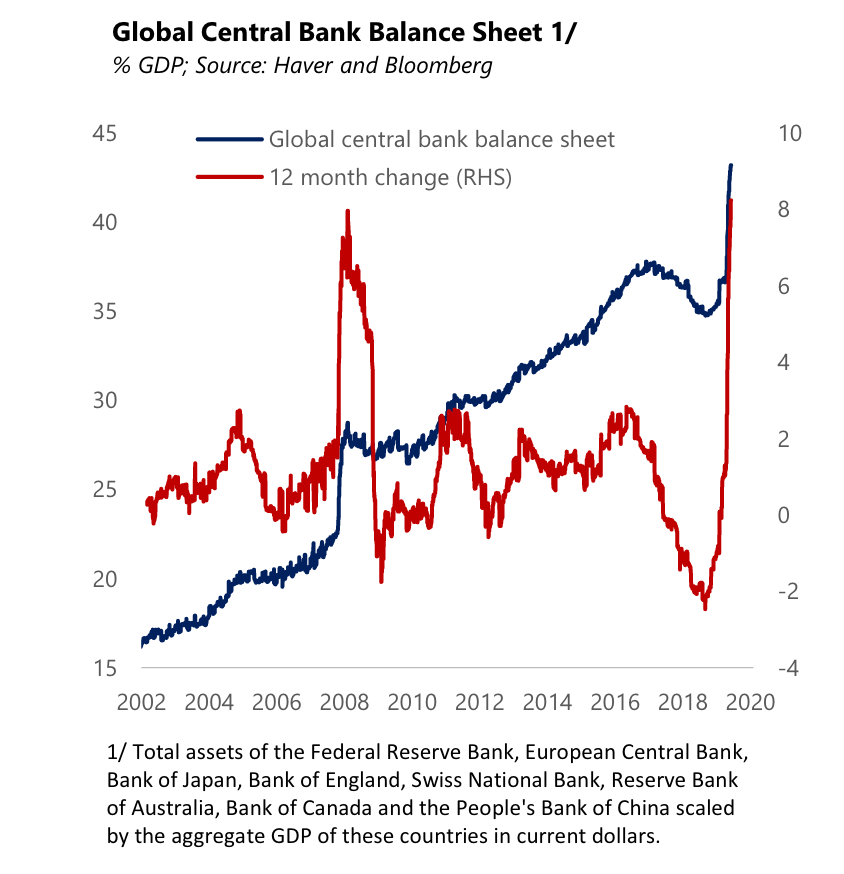

Monetary inflation is strictly an increase in the money supply. It’s undeniable that monetary inflation has been explosive over the last couple of decades and has accelerated past what many thought was possible over the last year. At the start of the millennium, central bank assets represented just over 15% of global GDP. By the time of the Great Financial Crisis of 2008 central bank assets represented close to 30% of global GDP and after the March 2020 financial collapse, central bank assets represented close to 45% of global GDP. This represents a 300% increase in the money supply in just two decades.

Central banks accumulate financial assets from the public and private sector as a last resort when there isn’t sufficient demand for these assets to keep systemically important firms and governments solvent and operational during financial and economic crises. CB’s accumulate these assets by simply creating more money and depositing the new supply in the accounts of systemically important firms and government coffers. These moves typically inflate the value of government bonds and systemically important financial institutions so they can continue to operate. If central banks didn’t step in during these times, overleveraged governments often wouldn’t be able to sustain the programs they’ve promised to their populations, and overleveraged financial firms would be insolvent, creating ripple effects across the economy acutely affecting industries, firms, and households who rely on bank credit to fund their operations.

These large-scale increases in the money supply don’t necessarily have to lead to noticeable increases in the general prices of assets or consumer items because they are often used to counteract the deflation of asset prices and enable government deficit spending. Although price levels might not increase and stay somewhat steady, as a thought experiment, the inflation can be found in the difference between the price level that was sustained and what the price level for assets would have been if central banks hadn’t recapitalized key financial institutions and monetized government deficit spending. This is precisely unknowable, but we do know in a general sense that if not for central bank intervention and monetary inflation, the prices of certain assets would have been much lower if not for their actions.

Asset Price Inflation

Unfortunately, there is no official measure of asset price inflation, and rises in asset prices are always left out of official inflation measures. Being able to accumulate assets at reasonable prices is key to building wealth over time and slowing down accelerating wealth gaps between asset holders and workers. For these reasons, we think they absolutely should be accounted for in official inflation numbers.

A measure that helps us get a sense of global asset price inflation is comparing the cumulative valuation of global equities to cumulative global GDP. Global equities are now worth 123.4% of global GDP, blowing past previous all-time highs made before the 2008 financial crisis and the dot-com bubble. In the US, home to the world’s most valuable equities and the world’s biggest economy, US equities are now worth 193% of US GDP, much higher than the previous all-time high of 159% recorded in 2000 at the height of the dotcom bubble. And wages in the US have not kept pace with these record valuations. From the early 60s to mid-80s, the typical American worker could work 30-40 hours a week and buy a unit of the S&P 500. The American worker now has to work about 140 hours to buy that same unit.

“Since the late 1990s, the ratio market value of the residential US real estate and domestic equities to Nominal GDP ranged between 2.5x and 3.75x times, nearly twice the level that existed in the prior 50 years. The tipping points for the tech and housing bubbles occurred at a ratio of 3x times. At the end of 2020, the ratio stood at 3.75x times, a new record.”

-Joseph G. Carson, Former Director of Global Economic Research, Alliance Bernstein

Similarly, residential real estate prices in Europe, Australia, Canada, and Japan are also at historic highs, notably in large cities. Global bond yields for government and corporate bonds are also at historic lows and in some places like Europe and Japan, bonds are yielding a negative nominal rate.

“The excessive increases in global asset and housing prices result from an exceptionally long period of extremely accommodative monetary policy. Many economists have noted, monetary policy is a key determinant of the financial system’s ability to create money. Money creation, credit creation and asset price determination are tightly interdependent.”

-Yves Mersch, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB & Vice-Chair of the Supervisory Board of the ECB

Consumer Inflation

Consumer inflation measures the general change in prices of a basket of goods and services over time and notably leaves out the asset price inflation that we discussed previously. Most countries’ consumer inflation rates range from 0.5% to 3% year over year, with some current exceptions like Turkey, Lebanon, and Argentina who are experiencing double-digit inflation. Venezuela is another notable exception that has experienced hyperinflation, with inflation rates in the thousands of percent every year for the past three years.

Although most countries are not experiencing hyperinflation, low consumer inflation numbers compound over time to make goods and services noticeably more expensive. An inflation rate of only 2%, sustained for a decade, leads to about a 22% increase in the average person’s cost of living in a decade. If the average person’s wages aren’t keeping up, their standard of living could start to noticeably decrease after a decade’s worth of work.

In addition to not including the inflation of asset prices, adjustments are made to consumer inflation calculations that often understate the actual cost of living. Official inflation numbers often include concepts like substitution and hedonic adjustments which allow government agencies to understate what many consumers experience when shopping.

Substitution recalculation takes place when a consumer chooses to substitute a similar item for an item they used to purchase because the item they previously purchased went up in price. If the price of steak went up and a consumer bought turkey instead because it’s cheaper than the now more expensive steak, inflation statisticians would count that as no inflation even though the price of steak clearly went up.

The idea behind hedonic adjustments is to incorporate quality changes into consumer prices. A product may be on the market at a higher price, but when the product qualities have improved statisticians will calculate that the price of this product has actually stayed the same or fallen. Applying the hedonic technique to a host of goods and services means that when prices are generally rising, the inflation rate can be recorded as non-existent because the product improvements are deemed to be larger than the price increases. Hedonic adjustments open the way to all kinds of manipulation due to the difficulty of measuring quality improvements in an objective way and governments having major interests in keeping official inflation numbers low because of cost of living based entitlements, government bond yields, and reporting productivity growth. For example, a new iteration of a coffee machine might go up in price but because it has bluetooth functionality, the inflation reporting entities can count that as a product improvement and report no inflation. It doesn’t matter if the consumer might not want bluetooth functionality as a part of their coffee machine, or that the bluetooth functionality doesn’t make the quality of the coffee any better.

Consumers should also be aware that inflation numbers are broad national aggregates and can be wildly different from your experience. You may not value the items that are going down in price and place a great deal of value in items that are becoming more expensive. And they could also wildly differ between regions because of factors outside of monetary policy.

The world is currently experiencing an explosive inflationary spike in many critical commodities including but not limited to lumber, energy products, corn, copper, soybeans, silver, sugar, cotton, wheat, and coffee. All are posting at least double-digit inflation year over year and some are easily in triple-digit territory. All of these commodities are key pricing inputs in a wide range of other products that producers and consumers alike purchase, so we shouldn’t be surprised if many if not all of our business costs and our cost of living inflate over the short term.

However, It’s hard to know if these price levels will continue on unabated, speed up, or even reverse course without zooming out and getting a long-term perspective.

The End of the Long Term Debt Cycle

According to research done by legendary investor Ray Dalio, we are near the end of a long-term debt cycle which lasts about 60-80 years. In his view, the end of the long-term debt cycle is looming when interest rate suppression and asset monetization (monetary inflation) have been exhausted by central banks and direct fiscal action must be relied on to maintain the economic status quo via aggressive deficit spending. Like clockwork, in the past 6 months, central bankers have made more explicit pleas to policymakers that they need more help from fiscal policy to maintain the economic machine.

Dalio says the currency that underpinned the long-term debt cycle is due for a devaluation at the end of the cycle and a change to the monetary order is typically on the horizon. In the case of our particular debt cycle, this means the US dollar is due for a devaluation and the global economy is on the cusp of a new monetary order.

However, other fiat currencies are not out of the woodwork, with their own massive debt levels equaling or even surpassing the United States. Governments with immense debt levels and slow growth rates usually choose to monetize their debts via accelerating money creation instead of allowing their economies to go through a painful deleveraging process. Over the past two centuries, 51 out of 52 countries that reached sovereign debt levels of 130% of GDP ended up “defaulting”, either through devaluation, inflation, restructuring, or outright nominal default, within a pretty wide spread of 0-15 years or so after that point.

Coda

If Dalio’s interpretation of the long term debt cycle is correct, massive increases in fiscal deficits that are monetized by central banks are very close to a certainty for the foreseeable future.

The important questions:

How effective will your government be with its deficit spending? Will it be able to spend in such a way that it expands the goods and services available to the average consumer while also contributing to technological innovation and long-term productivity growth relative to the amount of debt monetization?

If it can, then the average wage earner will be able to maintain their standard of living without a massive increase in consumer inflation while also avoiding a painful deflationary spiral. If your government can’t allocate the creation of new money in an economically productive way, then the average wage earner will experience rising prices over time and a declining standard of living.

I don’t know about your country, but I have very little faith in my government’s ability to allocate resources in a way that improves the productive capacity of our economy.